Revealed: a small but growing number of Chinese people are travelling to the Balkans with the hope of getting into the EU

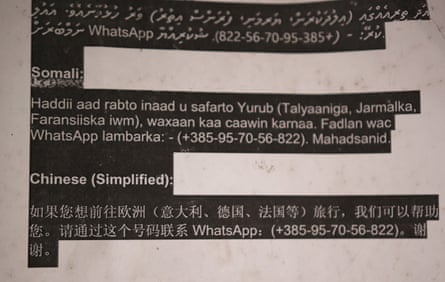

In a sleepy Bosnian town, barely five miles from the border with the European Union, a crumbling old water tower is falling into ruin. Inside, piles of rubbish, used cigarette butts and a portable wood-fired stove offer glimpses into the daily life of the people who briefly called the building home. Glued on to the walls is another clue: on pieces of A4 paper, the same message is printed out, again and again: “If you would like to travel to Europe (Italy, Germany, France, etc) we can help you. Please add this number on WhatsApp”. The message is printed in the languages of often desperate people: Somali, Nepali, Turkish, the list goes on. The last translation on the list indicates a newcomer to this unlucky club. It is written in Chinese.

Bihać water tower was once used to replenish steam trains travelling across the former Yugoslavia. Now it provides shelter to a different kind of person on the move: migrants making the perilous journey through the Balkans, with the hope of crossing into Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s neighbour in the EU.

Zhang* arrived in Bosnia in April with two young children in tow. The journey he describes as walking “towards the path of freedom” started months earlier in Langfang, a city in north China’s Hebei province. So far it has taken them through four countries, cost thousands of pounds, led to run-ins with the aggressive Croatian border police, and has paused, for now, in a temporary reception centre for migrants on the outskirts of Sarajevo.

The camp, which is home to more than 200 people, is specifically for families, vulnerable people and unaccompanied minors. As well as the rows of dormitories set among the rolling Balkan hills, there is a playground with children skipping rope and an education centre. But it is a lonely life. It’s rare to meet another Chinese speaker. To pass the time, Zhang occasionally helps out in the canteen.

“Staying here is not a very good option,” Zhang says, as his son and daughter chase after each other in the courtyard. But “if I go back to China, what awaits me is either being sent to a mental hospital or a prison.”

The fear of what the future held for him and his children propelled the 39-year-old from Shandong province on a journey so difficult and dangerous that many struggle to understand why someone from China would embark on it. Most of Zhang’s new neighbours come from war-torn countries in the Middle East. Until recently, Zhang had a stable job working for a private company in the world’s second-biggest economy, earning an above average salary. But the political environment in China left him feeling that he had no choice other than to leave.

In September, the Guardian travelled to Bosnia to meet some of the Chinese migrants attempting the dangerous Balkan route, to reveal the personal and political factors behind the new migrant population on the frontier of Europe.

‘No one wants to leave his country if they are safe’

Zhang is one of a small but growing number of Chinese people who are travelling to the Balkans with the hope of getting into the EU by whatever